Here’s what I’ve been working on recently:

Patchwork Approach

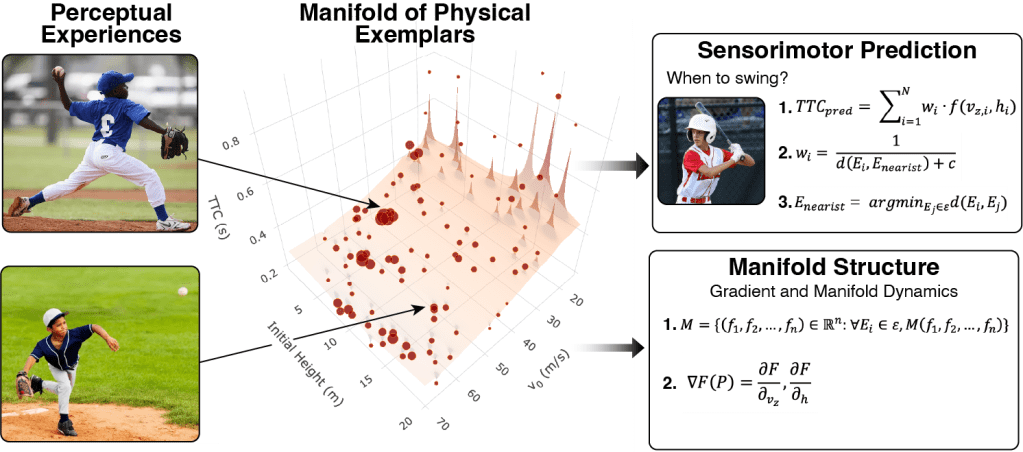

My “Patchwork Approach” to intuitive physics emphasizes how the brain tracks and identifies correlations among physical events. Rather than relying on fixed principles or classical mechanics, this approach highlights the brain’s ability to adaptively update its understanding based on new sensory experiences. This flexibility allows for a nuanced interaction with the physical world, optimizing our responses to dynamic situations.

Through my “Patchwork Approach” to intuitive physics, I move away from traditional views that rely on heuristics or simulations of classical mechanics. Instead, I demonstrate that our minds track and recognize correlations between physical events, forming flexible laws that adapt as we gain new experiences. This approach suggests that our internal principles of physics are shaped by real-life experiences, allowing us to make sophisticated predictions and interact seamlessly with our environment. As we navigate the physical world, we continually develop a unique “patchwork” of intuitive physics that, while distinct from classical mechanics, is optimized for practical interactions. As a next step, I build image-computable versions of the Patchwork Approach, using large-scale egocentric video and modern computer vision to extract the physical statistics that shape this perceptual manifold (see Computer Vision & AI below).

Computer Vision & AI

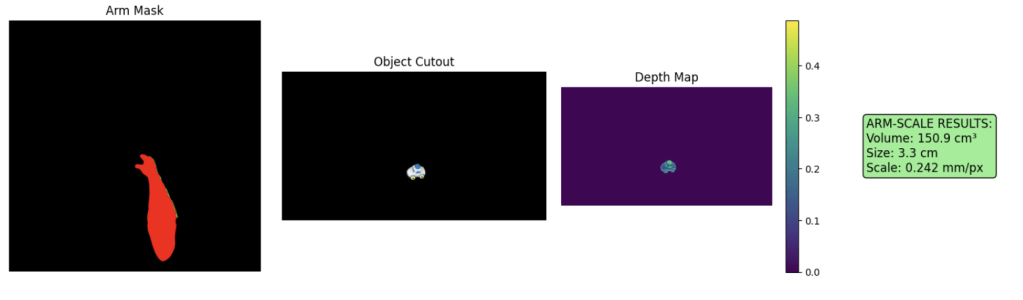

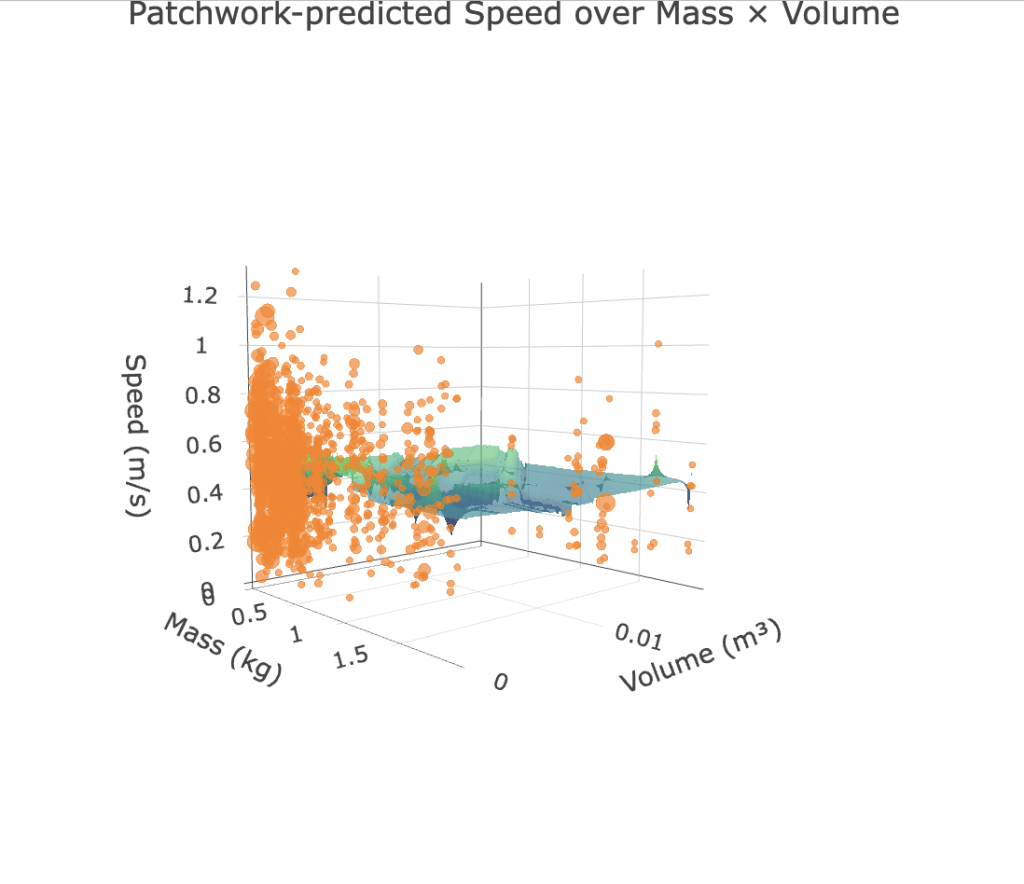

I extend the Patchwork Approach into computer vision, using egocentric video to estimate the same physical variables I study in humans. With modern segmentation and depth models, I extract hands, objects, and 3D structure from everyday interactions, turning pixel masks and depth maps into object mass proxies (e.g., volume, size) and velocity estimates over time.

These image-computable features become coordinates in a Patchwork model: each interaction is a point in a multivariate space defined by object size, volume, speed, contact duration, and other behaviorally relevant dimensions. By comparing human judgments to predictions from this image-computable Patchwork, I can test how well real-world physical statistics captured from video explain intuitive physics.

Gravity

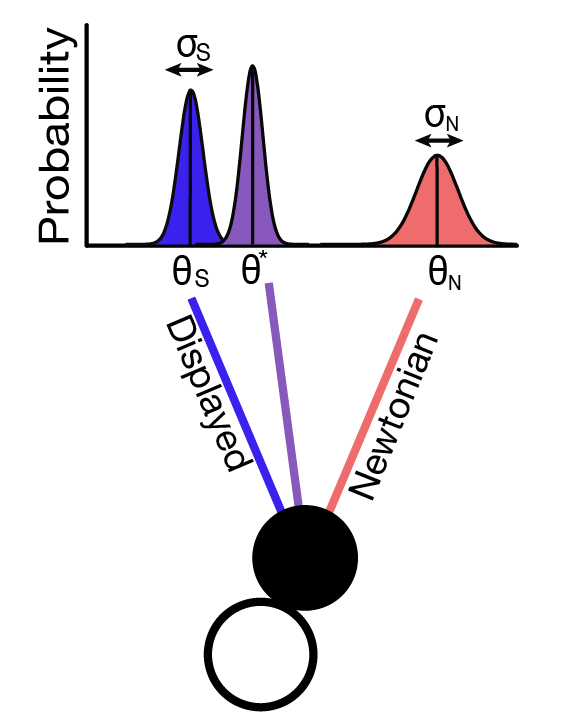

I’ve recently demonstrated how the visual system internalizes Earth’s gravitational constant. My findings reveal that the brain can predict the location of a falling object by simplifying complex relationships between initial velocity and gravitational force. This simplification suggests that our understanding of gravity is based on practical approximations rather than detailed simulations.

Angular Kinematics & Causality

I have shown that the visual system leverages regularities in angular kinematics to predict the location of launched objects. This finding illustrates how the brain internalizes kinematic principles, enabling effective navigation of complex physical environments. Additionally, these internalized regularities modulate lower-level spatiotemporal processing and guide smooth pursuit eye movements, highlighting the brain’s adaptability in using sensory information to inform real-time actions.

Mass & Conservation of Momentum

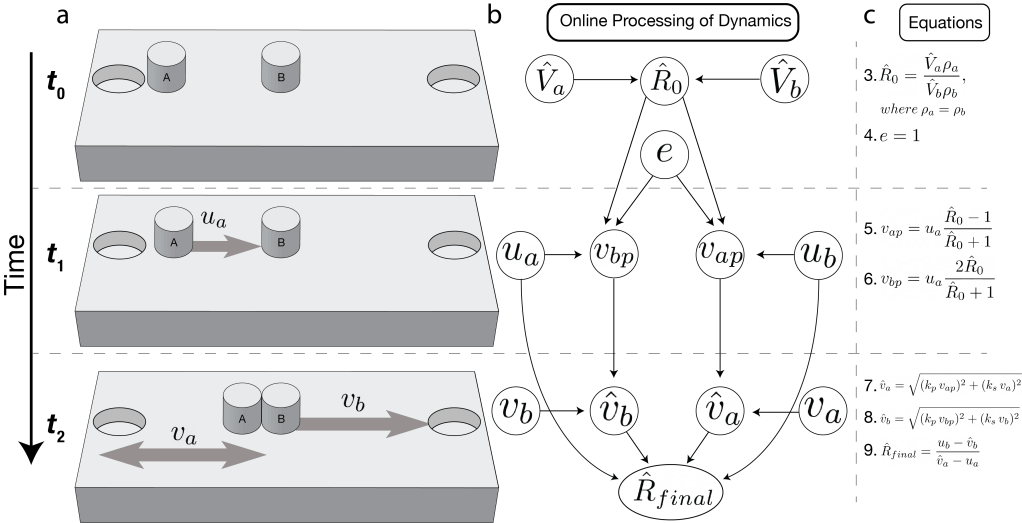

My research on conservation of momentum examines how the visual system perceives mass and influences motor object bias. I suggest that the brain infers object mass at different time points during a collision, beginning with the use of apparent volume to estimate mass before impact.

By integrating predicted mass with sensed initial velocity, the system generates a representation of momentum, enabling accurate predictions of post-collision velocities. This approach clarifies mechanisms behind motor object bias and phenomena like the size-speed illusion. Through empirical studies.

Perceived Velocity

I investigate how perceived velocity is influenced by perceived mass, particularly in the context of the size-speed illusion. Our experiences reveal that larger objects are often perceived as moving slower, challenging the notion that velocity is purely a spatial property. My research shows that the brain uses size as a proxy for mass, significantly impacting our velocity estimates.

For instance, smoother objects are typically judged to be heavier, and the lift speed of an object provides cues about its weight—slower lifts suggest heavier objects. These findings indicate that our mental representations of physical variables are shaped by statistical relationships in our experiences rather than adhering strictly to classical physics.

Understanding this bidirectional relationship enhances our insights into the cognitive processes underlying motion perception and may explain biases like the size-speed illusion. My experiments demonstrate that apparent mass directly influences how we estimate velocity, revealing how our perceptual system integrates these representations in dynamic environments.